Kati Roover is a Helsinki-based, multidisciplinary visual artist who in her work combines moving images, sound, photography and text. She draws from a wide range of disciplines, including natural science, feminist theory, philosophy and myths, with a particular focus on the interactive relationships between humans and non-human species as well as places and ecosystems.

Recently, Roover’s works have been exhibited in Finland, Germany, and Austria among other countries. She has participated in exhibitions at major museums and galleries, including the Museum of Contemporary Art Kiasma, Kunsthalle Helsinki, Turku City Art Museum WAM, and the Centre for Contemporary Art KINDL in Berlin.

In early March, Roover spent time in Budapest as FinnAgora’s guest, meeting local actors and working on her new project. We wished her welcome and discussed art, life and Budapest.

Nature has long been an overarching subject in your work – you deal with ecosystems and the role of humans in wider networks of actors. What drew you to these themes?

I’ve recently figured out a pretty good answer to this – namely, I went to a science upper secondary school in Porvoo. The teachers there were inspiring, and only now, 20 years later, do I realise that they’ve had a strong influence on my thinking. My Finnish teacher was fantastic, and my physics and biology teachers were also inspiring. For example, the physics teacher organised astronomy demonstrations and was absolutely fascinated by everything. In the end, it was a stroke of luck that I didn't go to photography school in another city.

world began opening up to me. I felt like no one was doing anything about it, so I went to the extreme and became vegan. But I realised a long time ago that you can only make a difference together – even ecosystems have to work collectively.

I’ve also grown up outdoors and seen a lot of different species. The place where I was born in southern Estonia, Põlva, has very special ecosystems and bodies of water, but there was always a threat present: the proximity of the border, the destruction of nature caused by war, and thunderstorms. In fact, the region is characterised by myths and traditions surrounding the thunder god. So it all started little by little, and now I'm on this path.

When did you realise that art is your way of dealing with these issues?

It required an ecological awakening. I was 19 years old when I got my hands on my first book about ecophilosophy, and after that the state of the

I think art is a good way of coming to grips with this theme and such difficult questions, although I am a little critical of its role. Simply doing art and analysing the situation is not enough – we also need collective action. Since the 70s we have known all the facts about what we are doing wrong, but it doesn’t seem to get through to people. Through art we can appeal to emotions.

Stories and mythologies have also served as knowledge for their time – they’ve just been dressed up in a particular language. I read quite a lot of research and turn all the information I collect into questions and poetics to evoke a sense of being at one with the environment. Many people feel disconnected, and it is this distance that I want to bridge.

You work a lot with video essays. How do you choose the medium for your art, meaning the methods and materials?

My interest in the essay film format was particularly influenced by Chris Marker's short film La jetée (1962) and Alain Resnais' documentary Nuit et brouillard (1956). La jetée is a beautiful film, although the subject matter is harsh. Through the essay format can be used to tackle broad and challenging issues.

At the time when I saw these films, I was painting and teaching painting, a period which left me with a sense of colour, light, and beauty. Nowadays my subjects have become more layered, but the medium lighter, eventually reduced to the pure light and sound that a camera captures. In my video works, I still build images like paintings, and the process often starts with dreams. I intuitively collect ideas from here and there, researching themes very broadly, and the subjects slowly start to take shape as images and collages.

What are you working on right now?

I have three works in progress, but one in particular is related to my stay here. It’s a video essay called Portals of Water (Veden portaalit), and I’ve been working on it for a long time. In it I draw on the idea of water as a portal to all realities – the same water circulating in everything. Water is also time, like the history of life.

In a way, I also think of it as a gateway through which I can examine these massive problems and how certain places have always been connected. Even humans move like water: along rivers, with the current, and following water. Water has influenced the birth and death of civilisations and evolution as a whole.

The work includes different water-related cultures, such as Estonia, Denmark, Iceland, Ireland, Finland and Hungary. These places have always been full of life and layers of time, and they have much in common: here in Budapest, for example, there are hot springs like in Iceland. After all, Budapest is a huge network of waters, different stories and layers.

Water is also a technical element in the video essay – as I edit different places together, I dive through the water to the next one. In a way, essay, sound and image together form a stream.

In your work you draw on theoretical approaches such as feminist new materialism, hydrofeminism, and animism. What ideas particularly interest you?

People often interpret feminism too narrowly, as if it only involved promoting the rights of women. Instead, what interests me is the broad question of what makes life possible on this planet, and how to preserve it. Strengthening equality reduces exploitative thinking, and the traditions you mention often consider longer time horizons. In animism, the idea is to take into account seven generations back- and forwards, which makes actions more deliberate.

Already for some time contemporary feminism has involved thinking in terms of ecosystems and planets. From a hydrofeminist perspective, we ourselves kind of are the places where we live – where we eat and drink. Because of globalization and the food cycle, we are both local and planetary beings. Over the ages, water has also circulated through all creatures on Earth, thus breaking down interspecies hierarchies. We carry the primordial sea in our cells – we are like water creatures on dry land, and we must constantly replenish our bodies with fluids in order to survive.

What about Budapest is special to you?

The city is composed of an incredible number of layers: history, water, and the life of humans among water. For local cultures water has always been special in some way. I’m interested in the local culture related to mineral water and the hot springs – the ways that people have existed near water in certain places in the past, present and future.

I only have a very short time here, so I don’t have time to do everything that I would like to.

Earlier you spoke of poetics and myths. Are you looking for them here too?

I’m interested in what the language of water is here, between the layers of time. We are living through really mythical times, so myths feel current. Many of the myths that are relevant to today came along just in time, thousands of years ago.

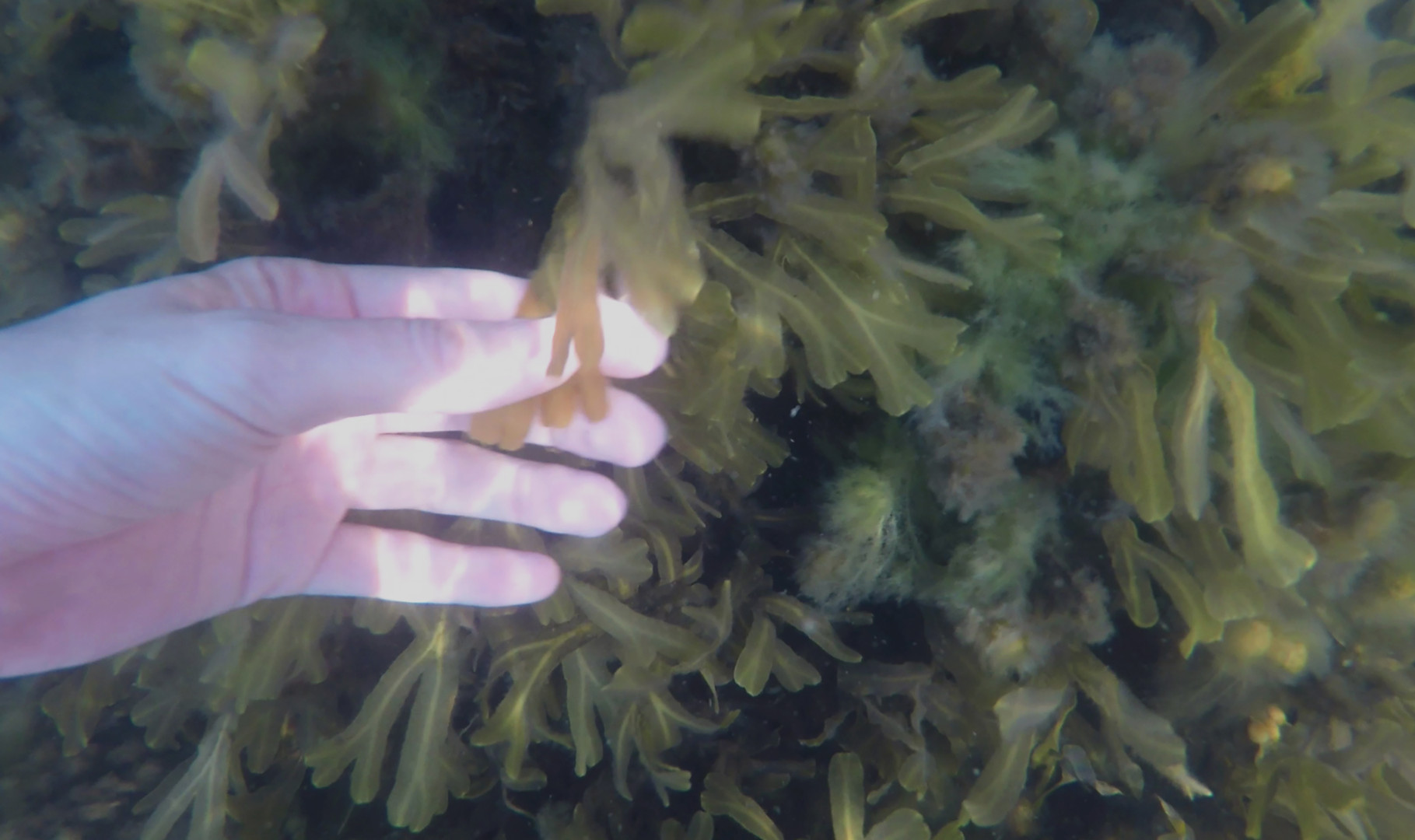

Still, we live in a world dominated by institutional knowledge. In your video essay The Scent of the Changing Sea (2020–2022) you utilise knowledge that is instead multi-sensory and experiential. How do you see the relevance of such knowledge in relation to the ecosystems you deal with, which are constantly changing and even threatened?

Let's think about how we got here: Europe’s history is full of instability, conflict and violent climates. From an empathic point of view, I can understand Decartes, who, in the midst of poverty, disease and death, wanted to rise above the human body. Coming from a family that has experienced a lot, I understand the idea that without a body, you would not have to carry traumatic experiences with you all the time.

In my own works I still always try to return to the body and embodied experience. I'm interested in materiality and haptics – for example, how sound comes to us. After all, sound is a vibration that literally touches us, and experiential information creates a certain kind of reality.

One of the things I have studied in my work is how whales experience their watery environment. While searching for videos on the subject, I found a site with almost perfect whales created by artificial intelligence. However, having been around whales and seeing them move and jump, I realised that these videos completely lacked gravity. The whales in the videos were just complete balloons. We have gravity, and AI has no experience of it – at least yet.

Whales also have a different internal experience from humans. In my work Songs in the Sea (Lauluja meressä), there will be a bench, from which sound travels to the body through the sense of touch. We often think that we only listen with our ears, but we always listen with our whole body – even through the sensory input from our skin and the vibration of the air.

Let’s jump to the future for a moment. What does this year have in store for you?

It’s going to be a really intensive year. The artwork I just mentioned will during the summer be exhibited at the Helsinki Biennial, where the theme is shelter. The exhibition will be cool, and Vallisaari Island, where the exhibition will take place, has a really special ecosystem.

With my video essay Coexistence (Yhteiseloa), I’m also part of the group exhibition Interferences at Kuntsi Museum of Modern Art in Vaasa, opening in the end of April. The theme of the exhibition will be the elements and energy, and my own work deals with the Amazon and our relationship to plants and language.

In May I’m participating in the exhibition Stories of Water (Vandets Fortællinger) at Rønnebæksholm kunsthal, and in the fall I and other artists working with water and the sea will have an exhibition at the Sopot Museum in Poland. Towards the end of the year, I’ll be back here in Budapest participating in an exhibition at the Ludwig Museum of Contemporary Art.

Is there anything else you would like to say before we finish?

We’re living in a time of the single story, but there have always been many stories – and they are networked, local, expanding, layered, and continuously changing. The loss of such multidimensional stories is a loss of biodiversity. In today’s world it’s important that humans give space to other species – this has a direct on us as individuals and on the environment we are dependent on. I also hope that we would take care of our local environment and the biodiversity that we ourselves are a part of. Biodiversity also means that we can have many simultaneous truths, even mutually contradictory ones. It is possible to live with paradoxes, mysteries and the unknown.

Who: Kati Roover

Place of residence: Helsinki

Occupation: Artist

Education: Master of Arts

Learn more about Kati Roover's work by visiting her website.

Text: Oskari Nyyssölä

Translation: Cecilia Fewster