Civic activism became ingrained in Joensuu-based comic artist and illustrator Sanna Hukkanen at a young age as she resisted racism and violence directed at refugees. While studying visual arts and later volunteering in Tanzania, Hukkanen's enthusiasm for the transformative power of community art grew. She sees comics in particular as an art form with a special ability to transform itself into a tool for advocacy and storytelling accessible to everyone. Over the years, Hukkasen has led comic workshops for different minority groups and civic activists around the world.

Hukkanen draws inspiration for her own comics from magical stories, the organic flow of forests, folklore, and old trees, which she loves to draw. Her drawings sometimes convey a dreamlike sense of inexplicability, where the boundaries between humans and nature blur. In addition to comic albums, Hukkanen has created illustrations for books, posters, magazines, and guides, and her work has been featured in numerous exhibitions.

In October, FinnAgora is delighted to welcome Hukkanen to Budapest, as her exhibition of Finno-Ugric grassroots comics, which has already toured Finland and Estonia, arrives at the Space of Opportunity for a month. The exhibition is based on the works created in Hukkanen’s and Anna Voronkova's Living Language community art project, and will also feature Hukkanen's own comics. Hukkanen will also hold a comic workshop at the Space of Opportunity on October 4th.

Hi Sanna! How did you discover your passion for comics and illustration? And when did you realize that comics can be used as a tool for activism and empowerment?

Perhaps even as a child, I knew that visual arts and drawing were what I wanted to do. I was a teenager in the 1990s when the first refugees arrived in Joensuu and there was a lot of racist violence in the city. At the time, I was involved in Joensuu’s Antifa and the anti-racism movement, and civic activism became deeply ingrained in myself.

I studied visual arts at the Karelian University of Applied Sciences, and comics began to feel like an art form that allowed me to combine activism and expressing my opinions with making art. For me, the messages expressed in comics seemed to sink in differently than, for example, from text alone.

I felt that the visual arts school emphasized terribly elitist views on what art is or should be. That world did not interest me at all. During my studies, I became interested in community art, where the artist is only there to facilitate something that a community creates. My interest led me and my friend to apply for a volunteer program through the Kepa organization (now Fingo). I ended up in Tanzania, doing a project study period for a local environmental organization. There, I worked on my thesis in visual arts and taught art with local artists.

I ended up living in Tanzania for a total of five years. There, I met Leif Packalén, the founder of World Comics Finland, who used comics in his work with non-governmental organizations. His association developed the grassroots comic book method that I use in my workshops. The method involves creating a four-framed comic strip, which is very easy to learn and requires only a pen and paper. It is therefore an inexpensive and accessible way to create art.

In Tanzania, I organized comic workshops for disabled groups through the Finnish Abilis Foundation. It was absolutely amazing. The situation for disabled people in Tanzania is very difficult, as disability may be hidden and considered shameful. It was eye-opening to see how making comics empowered the workshop participants, who had been told their whole lives that they can not do anything. They distributed their comics everywhere: at bus stops, markets, hospitals, and government offices.

You draw inspiration for your drawings from forests, magic, and even folklore. What led you to these themes?

It is partly related to my homecoming from Tanzania. My first very own comic album was called Juuri (“Root”), and it dealt with reverse culture shock and my family's story through four generations of women. The book contained many descriptions of the forest, mushroom picking, and being in nature.

Forest has always been exceptionally dear to me, and I have always loved drawing trees. Old trees in particular are amazing; their branches have an incredible rhythm. I can't draw cars, for example; they don't interest me in the slightest. There is something about the organic flow of the forest that captivates me.

My interest in folklore stems from the fact that the stories often portray humanity's connection to nature in a way that differs from our modern culture. They echo an animistic worldview, in which humans are not seen as separate from their environment. In my opinion, this would be a very healthy way of looking at situations and the world even today.

I am also interested in stories that take you to another level of consciousness and have a sense of the inexplicable. Folklore often suggests that humans can transform into other creatures, that the boundaries between humans and other creatures are fluid.

Your October exhibition in Budapest is based on comics created by Finno-Ugric minority language activists in your workshops around Russia, Estonia, Norway, and Finland. Tell us a little about the Living Language community art project!

In short, the whole thing started when my friend and I were on an organizational trip to Petrozavodsk in Russia. There we met Karelian language activists. For the first time in my life, I consciously listened to the Karelian language, and somehow the experience touched my heart and sparked emotion. Perhaps partly because it sounded a lot like the dialect my grandparents spoke.

It occurred to me that the comic book method might be suitable for linguistic minorities. I suggested organizing workshops for these activists, and they were enthusiastic about the idea. Later, they admitted to me that they had no idea what comics were and were surprised about the things you can do with it! Their preconception was that comics were some kind of Western propaganda, featuring American superheroes.

Anna Voronkova, whom I had met earlier while discussing another comics project, joined me on my trip. Anna studied Finnish at Moscow University, where she was told in a Finno-Ugric languages course that all these small languages had died out long ago. When Anna heard that I was going to hold a workshop for Karelian and Vepsian speakers, she was amazed and asked if she could come and see it with her own eyes! Together, we decided to apply for funding for the Living Language project so that we could hold workshops in other similar areas. Miraculously, we got the grant!

I could never have imagined that I would get to visit the places we traveled to. All the stories that the people we met told us about the Soviet era, their own folk traditions, and the difficulties they had with the state administration were eye-opening. I had no idea about any of these things.

On average, we met more young people in the cities, while in rural areas we met older speakers of minority languages. Young language activists were concerned about the disappearance of their language and cultural identity, and many had studied the minority language of their communities as adults. The young people brought the language into the present day, for example by organizing cultural events and thinking about how to make technology work in their language. In small villages, older people knew the language, reminisced old stories, and cherished traditions. In a funny way, these two sides worked well together.

Of course, all the stories from our travels were so interesting that we had to put them between covers for others to read. The people we met also expressed that it was extremely important to them that people in Finland knew about their existence. Some feared that the history of persecution against minorities would repeat itself someday. This inspired me to create the comic album, Taiga - An Ethnographic Travelogue, which I already drafted while sitting in trains during the journey. The creations from the workshops resulted in the book FUgrics – Comics from the Finno-Ugic World.

Is there a comic strip created in your workshops that has particularly stuck in your mind?

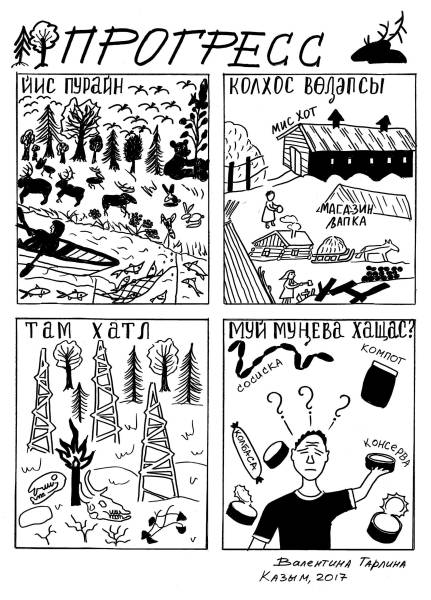

I could, of course, mention a variety of comics or workshops, but one that immediately comes to mind is a comic strip called Progress from the Khanty-Mansi region. It was created by an older lady. The comic strip first depicts the "old days," when people hunted and fished surrounded by animals and nature. Then came the Soviet era, with its shops and all else. Finally, the modern era and oil drilling arrive, and you can see animal skulls in the environment, everything is dead. In the last picture, a human is holding canned food and wonders what had happened.

I thought the comic was great because it had very little text. It expressed this whole long history in a simple way.

This workshop was in the Khanty region of Kazym, in northern Siberia. Kazym was a place that made a big impression on me anyway. Before the workshop, we were warned that the local "grannies" would not start drawing comics, as they were not interested in such things. We got the best comics ever.

Do you have any expectations for the comics workshop in Budapest?

I am open-minded about the workshop, but it would be nice if we could get as diverse a group of people as possible. Our partner in Budapest, the community art space Space of Opportunity, had the idea of inviting Roma activists to the workshop. I think that would be very interesting, because I haven't done anything with them before.

I am also interested in exploring what the political situation in Hungary looks like from the local perspective. Of course, I do not know how much the locals wish to discuss the topic.

What kind of projects are you currently working on?

I am currently working on two book projects. The first is my own project, a wordless comic book album, which discusses our connection with nature. The comic deals with transformations, forest’s networks, and urban nature through a werewolf story.

The second is a post-humanist fairy tale book in Karelian language for adults, which we are working on together with dramaturge Outi Rossi and Karelian language expert Katerina Paalamo. The tale features multi-species perspectives.

Who: Sanna Hukkanen

Lives in: Joensuu

Occupation: Comics and visual artist, illustrator

Lifestyle: Mushroom picking

Comic I recommend to everyone: Kuti magazine

Sanna Hukkanen and Finno-Ugric Comics exhibition: October 3–30, 2025

Comic workshop: Grassroots comics as a tool for community art: October 4th, 2025

Space of Opportunity, Práter ut. 63, 1083 Budapest

Photo: Kerttu Matinpuro

Text: Ilona Saarinen