FinnAgora is starting a series of interviews, where we publish a monthly interview with an interesting guest. The first interviewee in the series is Maria B. Raunio, Finnish artist and art teacher that has lived in Hungary for 20 years.

Who?

Name: Maria B. Raunio

Education: Masters degrees in painting and teaching visual arts and art history

Professional history: Artist, teacher of visual arts and art history in Budapest high schools and preparatory art schools, organiser and teacher of Portaan Akatemia and Szigliget’s art courses

Hobbies: studying languages, tennis, running, new recipes

Hungarian home towns: Zebegény, Budapest

Recommends travellers in Hungary to see: villages by the Danube Bend, cafes and galleries on Bartók Béla boulevard in Budapest

When did you first visit Hungary?

I visited for the first time in 1990 with my family and later with the youth choir I sang in.

And when did you move here?

I moved here in year 2000 so I’ve lived here for over 20 years. A few years ago we lived in Spain for a year, but besides that I’ve lived here ever since.

You’ve also lived in Italy and Japan. What made you stay in Hungary?

I first moved here because of my Hungarian spouse, and later I studied here so there were many things that connected me to this place. I’ve lived in Hungary longer than anywhere else, my active life has always been here.

When you moved here, did you face challenges or cultural differences?

Not really, ever since I was a child I’ve lived in multiple countries so I’ve learned what it’s like to face challenges and new things. So moving to a new country didn’t cause any problems. If you are receptive and interested in other people, most problems can be avoided.

With Hungary, it was the same. On the other hand, what made things easier was that I got to know my spouse’s circle of friends and that I quickly learned the Hungarian language. Wherever you go, the key to the society and well-being is knowing the local language.

How did you learn Hungarian - it has a reputation of being difficult to learn?

I started studying it on my own when I was in high school, as much as I had time for besides my school work. I also took some Hungarian lessons at the University of Helsinki. The teaching was very encompassing, it included history and culture, too. After I moved here I wanted to only speak in Hungarian with my Hungarian friends.

A year before moving I also started translating Hungarian folk-tales. I had been given a book of them, where the tales were in Hungarian and English, and I started making Finnish translations myself. It was very rewarding and motivating. I learned rich language that is not used in the every-day life but that taught me the language’s diversity and vocabulary.

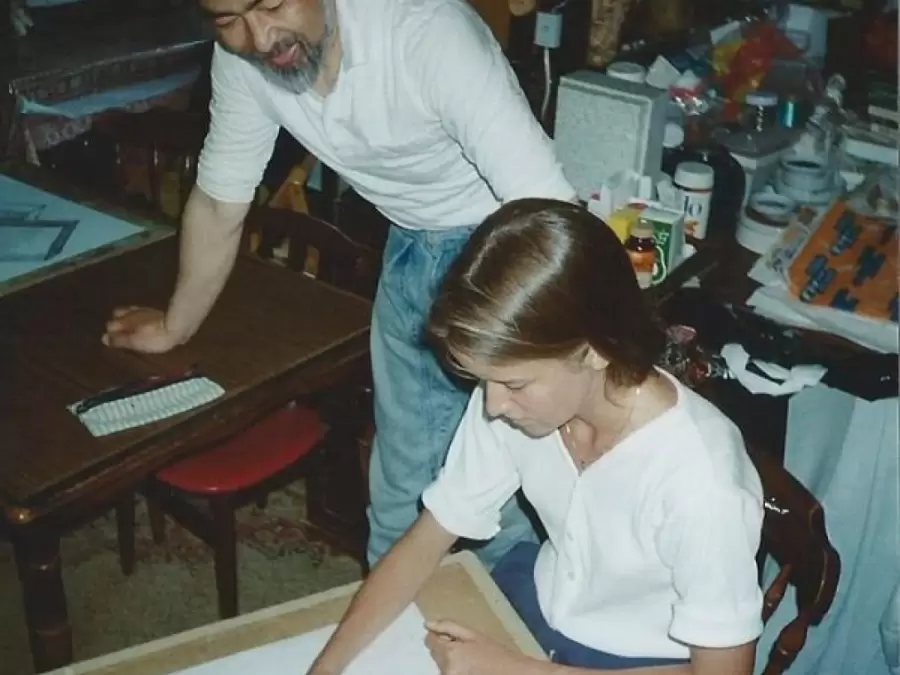

Raunio with her students (dressed in white on the left side).

Has Hungary changed while you’ve lived here?

Nowadays Hungarians pay more attention to health, exercise more and eat healthier. Lately I’ve also started noticing that Hungarian often speak of the problems they see, but they don’t want to act to change them. As I’ve gotten older I’ve realized I have to take responsibility for changing the things I don’t like. I’m sure this phenomenon has existed for a long time. How I see Hungarians and the Hungarian society reflects what I am like myself, and how I think in that moment.

What have you learned from, or especially value, in the Hungarian society?

I respect a certain type of healthy attitude towards culture and historical thinking. The fact that history is a compulsory subject in the matriculation examination and the active culture life in Hungary show that these things are respected here. I think all subjects should be taught from a historical point of view so that we understand ourselves, the society and the world as a whole.

Another thing that is important to me is comprehensive education of art. Unfortunately it has been brought down here in Hungary too, as well as the rest of the world. This is a concerning tendency because we are raising policy-makers as well as citizens, and studies show that art teaches us many things such as creativity, social skills, empathy and problem solving. Regardless of this tendency, I think art is still appreciated here. It is also something that is close to my heart and that I want to work for.

Do you consider both Finland and Hungary your home countries?

I do, I’ve lived here for a long time. A week ago I got back from Finland and for the first time I felt like I could return there and feel well there as well. It affirms the feeling that my home is not a singular, physical place in the world. I’ve been living a time of change in other ways too, my daughter is now 19 years old and as a freelancer I have the freedom to go wherever life takes me. That is a fantastic feeling.

You have experience of both Finnish and Hungarian school system as a student and a teacher. What are the differences and similarities between them?

Teaching in the Hungarian system is traditional and hierarchical with a focus on manners and diligence. School days are long and the students have to study a lot. In the top high schools in Budapest the teaching is different from schools in more remote rural areas. In Hungary there is a lot of compulsory reading and the focus is on educating talented students, which is why many top experts come from here even though Hungary doesn’t usually place high in PISA studies.

The good thing about the Finnish system is that teaching is democratic and fairly homogenous everywhere. Comprehensive teaching is strong and everyone is treated the same. Both have their pros. I am very happy that my daughter has gotten her comprehensive education and good prerequisites for studying here.

In Finland there is a will to constantly evolve, but that is not an intrinsic value: reforms don’t necessarily bring results, if the schools can not keep up with them. I don’t wish Hungary would operate in the same way. The results of PISA studies don’t show what works here: very throughout teaching of literature and history. They are also compulsory subjects in the matriculation exams. They make us human and are something I wish nobody ever intervenes with.

On the left an artist meeting in 2020 (photo by Judit Kallós). On the right Raunio with her daughter Joli.

Are your different home countries somehow reflected in your art?

For sure, but how they are reflected in my art equals how they are reflected in myself. Right now I make paintings through memories and by abstracting and I don’t plan precisely how I want the result to look like. The process is free and guided by intuition. It’s difficult to say where everything that ends up on the canvas comes from.

The upside of having multiple places in the world where you can be well is that changing locations helps to break my bubble that I otherwise can stick to very easily. Stepping outside your comfort zone gives a different perspective.

After every trip I notice that I see Hungary in a new way, and that is extremely important for my art. The trap of well-being is that you don’t test yourself or take up new challenges.

Do you feel like making art is easier in a place like Budapest, somewhere with a rich cultural life and constant opportunities to see art?

Yes, but that also makes you compare and puts you in a constant dialogue with what you see. Nowadays this happens anyway because of the internet. On the other hand in a place like this there is a lot of talk of what kind of chances an artist has with so much competition. These are thought patterns that only limit what you can do.

It is an asset that there are so many artists. In university there was talk of whether educating this many artists is necessary, but this is also a question of whether art is necessary. Of course it is! Whatever art students become, they often have the right values and mentality.

You’ve worked with art in a very multi-faceted way: as an artist, a teacher and an organizer or art courses. Do you still dream of working in some new sector of art?

Yes, but my dreams don’t have to do with career or fame but inner motivation. For example, I’d like to make new learning material for art education, not only for kids but for adult education as well. I’m worried about the decline of art education and I see it as my responsibility to also do something about it. However, the most authentic and important thing is what I am currently doing: making art.

Salla Hiltunen

FinnAgora